Click here to view/download this page as a PDF

Chapter One

Prelude:

Opening Credits and Advertising

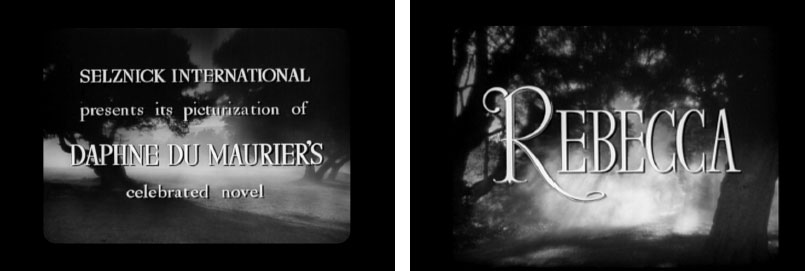

The opening credits of Rebecca pay homage to the author and the novel upon which the film was based. Instead of the usual terminology “based on the novel,” the first credit shown on the theater screen -‐ before the main title – states:

SELZNICK INTERNATIONAL

presents the picturization of

DAPHNE DU MAURIER’S

celebrated novel

The title REBECCA is emblazoned against the background of what we will come to recognize as the overgrown Manderley estate in the following shot. The use of the word “picturization” is especially significant considering Selznick’s expressed intention to be extraordinarily faithful to du Maurier’s novel in making his film. The term was used in the credits of some early silent films that had been adapted from famous literature, but interestingly, had not been used in Selznick’ International’s two earlier major films based on popular novels, Frances Hodgson Burnett’s Little Lord Fauntleroy or Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind.

When a mansion is an important part of a novel, it is generally the book’s cover illustration. When a mansion is an important part of a movie, it is often introduced in the opening credits or the opening scenes of the movie. An image of the mansion, as well as its stars, may be features in newspaper advertising or displayed in its lobby card posters. The mansion is often shown or mentioned in the movie’s trailer, previewing it to theater audiences and so it was in the promotion and presentation of Rebecca.

Two of the many dozens of lobby posters made for the film

In the poster on the left Manderley appears in the bottom left corner;

on the poster on the right it is seen in the upper right quadrant.

Chapter Two

Portrayal of Past, Present and Future Time:

Use of Prologue or Flashback in Mansion Movies

The Opening Scene with Voice-‐Over Narration

The movie opens with a hazy view of a wooded landscape and the soft female voice of the narrator describing going back to Manderley in a dream. We hear the oft-‐quoted words “Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again.” We do not see the female protagonist, but see the unfolding dream through her eyes; the eye of the camera is the both the eye of narrator and the eye of the film spectator at the same time. On the screen before us is the scene described by voice-‐over narration. Through the unseen woman’s eyes we see and magically enter through a pair of ivy-‐ covered wrought iron gates set into a curved stone archway stone with walls on either side. It is through this outer barrier that we the audience first enter the story.

By means of the lens of a forward moving camera, we proceed down a winding, overgrown driveway. Then before us in the distance, we see a huge mansion in ruin silhouetted against a night sky. The mansion fills the entire screen. It is a seen in through the mist, a desolate shell but still impressive and hauntingly majestic. The camera pans across the front façade of the building and focuses on a light that seems to come from within, but the narrator suggests, is just a reflection of the light from the moon.

“There was Manderley, our Manderley, secretive and silent as it had

always been, the grey stone walls shining in the moonlight of my

dreams, the mullioned window reflecting the green lawns and terraces.

Time could not wreck the perfect symmetry of those walls…

Dreamscape silhouette of the ruined shell of Manderley

Dreamscape silhouette of the ruined shell of Manderley

The dramatic and mysterious opening introduces us to Manderley and foretells its ultimate state of ruin by the end of the story that follows. In the course of the film we the audience will go back to Manderley again; the camera will travel down this very drive and arrive at Manderley two more times. At the end of the dream sequence, the narrator shifts from describing her dream to an earlier time, remembering the real events that occurred before Manderley became part of her life.

Reconstructing, remembering, and recounting experiences or events that have occurred in the past is of great importance in mansion movies. In these films it is essential that background information be somehow conveyed to the film audience in order to understand the main plot. Often the mansion insiders are presented as living in the past. Their family history and their position in society have a significant impact on their present day issues. The outsider protagonists who arrive at and enter the insider’s mansion home in each of these films also carry with them unfinished business from the past. The outsider’s arrival brings fresh air from the outside world into the enclosed private world in the mansion. More importantly, the outsider’s arrival changes the status quo for everyone involved, insiders and outsiders alike.

The Past Told as a Flashback

Some film historians and reviewers refer to the opening dream sequence in Rebecca as a “prologue,” treating the remainder of the film that is conveyed in normal chronological time as the main plot. Mansion movies often use a prologue, signage or other filmic devices and conventions to provide a backstory explaining the history and motivation of the characters in the plot that unfolds in linear time. However, in Rebecca, time is not presented chronologically. We are told what will happen in the future, although the last words spoken at the end of the dream reference Manderley as a memory, a place in the past. Despite its placement at the outset, the opening dream sequence is more like an epilogue. The unseen narrator is speaking to us in her present time letting us know how the story ends before we even know its beginning.1 In doing this, the film follows the time line of the first two chapters of du Maurier’s novel; however, the rest the novel is recounted as its heroine’s first person remembrance of what has already happened. In Rebecca, the movie, the opening dream is an essential part of the plot, deliberately showing us the ending in advance. We see a once magnificent mansion left in ruin amidst the abandoned and overgrown grounds of its surrounding private estate; before we know anything, we know something has been lost. In both the film and novel the story is presented as one flashback, albeit an extremely lengthy one. The film diverges from the novel in that the events enacted by all of the characters in the story as if occurring in present time, as opposed to being conveyed in first person voice of the heroine. The effect of this is that, despite what we are shown at the outset, the audience suspends its knowledge of the ending while watching the rest of the film.

Chapter Three

The External Everyday World:

Going Back to Another Place and an Earlier Time

In a starling change of sound, sights and surroundings, the flashback first takes us to the southern coast of France near Monte Carlo. A lone distraught man (Laurence Olivier) is seen at the edge of a cliff seemingly ready to jump. We hear a voice, the voice of the narrator, spontaneously shout out to stop him from doing so. Then, we see the figure of the young woman (Joan Fontaine) who called out to him. We now connect a body to the voice which described her dream in the first scene. The man harshly scolds his would-‐be rescuer and orders her to go away and leave him alone.

The next scene is opens against the exterior of the Princesse Hotel in Monte Carlo. The detailed and dazzling presentation of the imposing facade of the hotel and its ornate interiors gives the audience an insight into the life of luxury and leisure of the wealthy travelers to European resorts in the first quarter of the twentieth century. In most mansion movies, the external world is the public everyday life of ordinary people as opposed to the interior privileged world of mansion insiders. However, in this film the external world is a lavish holiday resort the elegant images of the hotel will later be paralleled and then eclipsed by the images of Manderley to come. In these scenes, and almost all scenes other than those at the mansion, the camera work is distinct from the camera movements once inside Manderley. We the audience are spectators watching the scenes projected on the screen; there is an emotional distance between the audience and the action on the screen. We the audience do not enter into the hotel through its revolving entrance door, nor do we sit or stand in tandem with the protagonists in the various other Monte Carlo settings. We watch the events portrayed on the screen as mere observers, nosy onlookers or ease-‐dropping voyeurs. The action is presented as if played out on a theater stage, with an invisible fourth wall between the actors and the audience. In the mansion scenes to come later, the moving camera will effectively bring the audience into the various rooms of Manderley; we the audience will feel as if we are participants with the characters inside the space, rather than spectators.

1. This treatment of time also appears in Sunset Blvd in an even more unconventional way; the narrator speaking to us is the dead man we see floating in a pool; moreover, he narrates his inner thoughts in telling of his story throughout the remainder of the film.

Introductions: Maxim de Winter and Mrs. Van Hopper

Introductions: Maxim de Winter and Mrs. Van Hopper

While seated in the lobby of the Hotel de Paris in the company of an older woman (Florence Bates), the young woman we saw in the previous scene recognizes the man walking through the lobby as the figure she saw on the cliff. Her companion also recognizes him and announces his name, Maxim de Winter. The woman introduces herself to de Winter as Edythe Van Hopper, reminding him that they had met sometime before at another international society resort. Our heroine, however, is not introduced at all –neither to Mr.de Winter nor to us. Quite deliberately, she remains nameless throughout the film. The novel is written as a first person narrative, i.e. “I thought,” “I was glad,” “I dreaded,” etc. (In her book The Rebecca Notebook & Other Memories written forty years after Rebecca, du Maurier explained that at first she simply could not think of a name for the character. She later chose to leave the character unnamed as a “challenge in technique.”) As other people in the story never identify the heroine by name, neither her first name nor her maiden surname are ever uttered. Her character was denominated as merely “I” in the screenplay. Since the movie’s premier, this character has consistently been referred to as “I” in articles and reviews; she shall remain identified by the pronoun “I” in this study.

When Mrs. Van Hopper mentions she last saw de Winter at the casino in Palm Beach, he explains that gambling no longer amuses him. She responds that if she had a home like Manderley, she would never come to Monte Carlo. She goes on to say she’s heard it how big it and how beautiful Manderley is. “I” later learns from her employer’s gossip that de Winter has been a recluse and away from home since the tragic death of his wife, Rebecca. In contrast to our heroine, Maxim de Winter’s deceased wife is fully identified by name as the “beautiful Rebecca Hildreth” before becoming Rebecca de Winter upon her marriage.

Chapter Four

The Outsider’s Moment of Crisis:

A Turning Point Initiating the Journey

Mrs. Van Hopper quickly comes down with the flu and hires a private nurse to care for her. While her employer is bedridden, “I” is left on her own. Despite the lack of an initial introduction, de Winter invites “I” to sit with him when he sees her sitting alone in the hotel’s dining room. We learn “I’s” mother died when she was a young child and her father recently passed away. Other than the temporary accommodations provided by her employer as a companion, she is homeless. Maxim offers to show her around the Rivera countryside in his car. They quickly get to know a little bit about one another. They meet alone and often. He is charming but moody; she is shy but earnest. On one of their excursions he speaks of Manderley, his ancestral home. When Maxim talks to her about his home in Cornwall, “I” reminisces that she once purchased a postcard of Manderley while on vacation as a child and that picture of the place has remained in her memory.

“Manderley“, “Manderley“, “Manderley” -‐ the name of the mansion -‐ will be said over and over throughout the film. Before we see the building again on the screen we will have heard its name at least eight times.

The couple continue to see each other and their meetings evolve into a whirlwind holiday romance, as Van Hopper remains bedbound and recuperating. Their time together is cut short when “I’s” employer suddenly learns of her daughter’s engagement. Van Hopper announces to “I” that they will be leaving immediately for New York to make wedding arrangements. Upset with the unexpected news and the prospective end of her holiday romance, “I” frantically tries to find Maxim to tell him goodbye. Emboldened by the urgency at the imminent departure and the distraught belief she will never see him again, “I” goes to his hotel room. It is unstated, but “I” seems to have an inner sense that this aristocratic man can in some way save her. When Maxim hears what is happening, he bluntly offers her a startling proposition. He asks if she would prefer, “New York or Manderley?” Not understanding what he means, “I” incredulously asks if he is looking for a secretary. He clarifies that he wants to marry her. Still amazed, “I” tells him she doesn’t belong “in his sort of world.“ “What is my world?” he asks. She responds “Well Manderley, you know what I mean…”

Interestingly, Maxim offers her Manderley -‐ his home -‐ in place of or perhaps as a part and parcel of how he identifies himself. For her, the house defines his world, a world he has invited her to share with him. He never mentions his own feelings for her, but when she does not immediately answer, Maxim suggests that she might not love him. “I” unabashedly and plaintively declares her deep feelings for him. Her surprised and delighted response to his proposal seems to flow both from her infatuation with the dark handsome stranger and the remembered postcard vision of Manderley.

Is it possible that women in the past, and possibly the present, fall in love with and marry real estate? Arranged marriages were based on property considerations on both sides. Jane Austen’s novel Pride and Prejudice was written when landowners rather than entrepreneurs were the predominant class and women’s options were limited. It always stuck me that its heroine, Elizabeth Barrett, seems to reconsider her earlier disdainful attitude toward the arrogant Mr. Darcy when riding though Pemberley and upon learning he is the owner of the vast country estate she has long admired. Author Marjorie Garber confirmed my reading of Elizabeth Barrett in her intriguingly titled, Sex and Real Estate: Why We Love Houses. Pemberley, Mr. Darcy’s ancestral home, like Manderley, is the symbol of the man who owns it. Fans of the popular British television series Downton Abbey, will remember Lady Mary’s conflicted thoughts about marrying Matthew Crawley to hold onto her family’s beloved home when, because of inheritance laws, he became Downton Abbey’s rightful heir.

In Rebecca, Mrs. Van Hopper’s sudden change of plans created a momentous turning point in the life of “I.” In mansion movies, a precipitating event in the life of an outsider protagonist results in the hero or heroine’s journey from the outside world to the mansion destination at the center of the story. Maxim de Winter ‘s chance meeting with “I” in Monte Carlo, his finding happiness again in his brief relationship with her, is also a turning point for him that leads him back to Manderley. There chance meeting ends his year of self-‐ exile after the death of his wife and realizes our heroine’s fanciful dreams; not only will she marry a prince, she is will gain a fairy tale palace as home. “I” is looking for a home; Maxim is yearning to return home.

Her happiness at this is momentarily shaken by her employer’s disparaging forebodings of failure regarding the proposed marriage. Mrs. Van Hopper laughs out loud at the prospect of her young companion as the mistress of Manderley; she later suggests Maxim is not in love with “I,” but merely annoyed by an empty house. Thus, Mrs. Van Hopper also equates the proposal to a marriage to Manderley and her comments foreshadow the reality “I” will encounter when she arrives at her journey’s end. Mansion movies are often in part fairy tale stories. Rebecca starts as a Cinderella story. At the opposite end of the spectrum, mansion movies may be haunted house or horror stories. Once at Manderley, Rebecca becomes a combination of both.

Chapter Five

The Heroine’s Journey:

from Monte Carlo to Manderley

Mansion movies are also mythological tales following the paradigm of Joseph Campbell’s celebrated thesis on the “the hero’s journey” in ancient narrative stories throughout the world. In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Campbell studies myths in which the hero ventures forth from his ordinary world, a known world, to a different and unknown place, facing hostile forces, trials and challenges in the quest for a place, person or object. In these tales, if the hero decides to return home, he will face further challenges, but also brings back special knowledge and a benefit or gift to the community he once left.

The hero in mansion movies can be male or female. Mansion movies are generally told from an outsider’s point of view, someone with whom the audience will identify, rather than with the more privileged mansion insiders, who are initially regarded as less sympathetic characters. To avoid confusion when describing and discussing the protagonists in this and other mansion movies, I will refer to the story’s female outsider as the heroine, and, when applicable, the male outsider as the hero. Occasionally, a mansion insider considers him or herself an outsider, someone who does fit in or belong. Also, as there are usually both strong male and female leading characters in these films, the terms hero and heroine are used to identify the gender if there both male and female leading characters. The term “heroine” is especially useful in discussing Rebecca as the female lead has no name. My favorite childhood books were Frank Baum’s tales of Oz. Baum’s Dorothy takes possibly the most memorable hero’s journey in Hollywood film history in The Wizard of Oz (1939). Like Dorothy when finally reaching the magical Land of Oz, our heroine in Rebecca will discover that the postcard kingdom of Manderley will not be all that she had hoped.

In mansion movies, as is sometimes true in the hero’s journey sagas or “road” movies, the geographical trip to the mansion destination at the literal journey’s end, is often just a very brief part of the story. There is initially a short physical trip from the starting point of the hero’s or heroine’s story to the movie’s mansion setting, but that trip it is a mere precursor to the hero or heroine’s emotional and psychological journey, or personal transformative experience -‐ that begins only once the mansion is entered. In Rebecca, immediately after the proposal and announcement to Mrs. Van Hopper scenes, we next see Maxim and “I” as they are leaving a town hall, somewhere in the south of France, just after their marriage by the local magistrate. From this point they commence their honeymoon trip through France and perhaps Italy. (The novel indicates they went to Venice as part of the trip, but as in the movie, the honeymoon is scantily described.) The audience sees very little of their actual journey from Monte Carlo to Manderley, on the southwest coast of England in Cornwall. other than the brief glimpses of their honeymoon shown in retrospect in a later scene of Maxim and “I” watching a home-‐ movie of that brief happy time. Instead, the story shown on the screen fades out just after their marriage in France and fades in just as they are approaching the estate gates to Manderley.

This capsulized honeymoon journey and everything which happened and or was said before is anticipatory to their arrival at the mansion where the main event -‐ “I”s inner trials and challenges inside the mansion -‐ commence. On arrival at Manderley, we begin the central story of Rebecca where a typical fairy tale would end. Instead of the story ending here at the mansion with the words “…and they live happily ever after,” the “ever after” is just about to begin.

Chapter Six

Arrival at the Mansion:

“You Have Reached Your Destination”

The first threshold: going through at Manderley’s entrance gates

The first threshold: going through at Manderley’s entrance gates

Anticipation of the arrival at Manderley has been built in the preceding scenes: our heroine knew her home-‐to-‐be from a post card purchased in her youth, heard Mrs. Van Hopper’s glowing descriptions of the place and was privy to Maxim’s invocations of Manderley as home. Now the moment is at hand. Her anticipation is mixed with apprehension and anxiety. Although we in the audience already had a preview of Manderley in ruins in the opening dream sequence, what we have been watching since that opening scene was part of a long flashback that began on the cliff near Monte Carlo which will continue through the rest of the film.

The first border crossing in the journey to Manderley occurs at the estate’s magnificent formal wrought iron entrance gates set within the stone archway of a gatehouse with lodging rooms on either side above. Although not shown on the screen, we can imagine that, beyond the film’s frame, the stone walls on either side of the gates encircle the perimeter of the land boundary of the estate and that this gateway is either the only or one of a limited number of points of entry. The mansion’s realm extends to the outer limits of the grounds marked by these gates and walls. As the car approaches, a gatekeeper prepared for the couple’s arrival, unlatches the gates and swings them open. Metaphorically, the arms of the estate opened to welcome its absent owner and his new wife home. Once inside the gates, we have crossed the outer boundary of a separate world. The new bride and groom, together in an open car, are driving happily along the winding road first introduced in the dream sequence but this time the driveway is well kept and the grounds are lush but trimmed. It is not only just by an accident of nature that the interior roads of great estates are circuitous rather than a straight line from entry gate to front door. Estate drives were often specifically designed to curve and wind through landscaped grounds, lengthening an already long approach drive, in order to give the exaggerated impression of an even vaster expanse of land. Doing so heightens the visitor’s anticipation of what lies ahead.

When they are almost home, it begins to rain. Maxim covers his bride’s head with his raincoat to protect her in his open-‐roof car. Around the last curve, Manderley appears in the distance, filmed by the camera and first glimpsed by “I” and the audience, through the fan-‐shaped frame created by the car’s windshield wipers. In this arrival scene, we in the audience are taken back in time to the heroine’s very first sight of her husband’s ancestral home. In a sense, we too have the sense of seeing Manderley for the first time through her eyes. Maxim exuberantly announces, “That’s it, that’s Manderley!” and the camera shifts to a close-‐up reaction shot of the bride’s expression of sheer awe.

The mansion seen through the arc of a rain-‐swept windshield and the heroine’s reaction

The mansion seen through the arc of a rain-‐swept windshield and the heroine’s reaction

The camera then shows the mansion’s front facade filling the entire movie screen. This is one of the most powerful “wow” moments in any mansion movie. The first full sighting of the mansion in a mansion movie is a special scene, whether or not the mansion plays a role beyond being a mere setting or background. It is almost always a climactic moment of visual sensation. Even though we saw Manderley as a ruin in the opening scene, we are seeing it here for the first time in its full glory.

“That’s it! That’s Manderley!” Shown in the rain-‐ its massive façade filling the screen

“That’s it! That’s Manderley!” Shown in the rain-‐ its massive façade filling the screen

The movie mirrors our own real life sensations of the view when coming onto a crest of a hill, all at once seeing a broad vista for miles ahead, seeing a world-‐famous painting for the first time in a museum, or opening a gift box and seeing a beautiful jewel, and being bedazzled. To accentuate the impact of the arrival, the musical score by Franz Waxman, swells to a triumphal crescendo when the image of Manderley is emblazoned across the movie screen. (Throughout the film, Waxman’s score expresses the different moods, settings and characters set forth in the story through tempo and tone. He described his work for Rebecca as his favorite of the some one hundred forty-‐four Hollywood film scores of his long career.)

The overwhelming monolithic presence of the mansion, along with the dramatic music, establishes the building as the centerpiece of the story, the setting being equal in importance to the movie’s major stars. As the newlywed couple drive closer to the house, the camera pans out in a long sweeping shot of the house as their car, dwarfed by the enormous mansion, moves from left to right along the monumental stone walls of the massive building. The camera moves slowly to highlight the impact and allow us time to absorb Manderley. The audience directly feels the visceral impact of the house as well as vicariously experiencing the heroine outsider’s sense of being overwhelmed upon seeing the house for the first time. In The Hollywood Eye: What Makes Movies Work, Jon Boorstein explores the art of making films and how the audience looks at films through the “voyeur’s eye,”), the “vicarious eye” and/or the “visceral eye.” In my interpretation of his thesis, in our first glimpse of Manderley with the long shot, we experience the pleasure of seeing something fascinating from a distance or voyeuristically. Then, in sympathy with the feelings of the character on screen, we experience the moment of awe vicariously through the expressions and reactions on her face. By the time the scene ends, with Manderley’s image filling and even going beyond the boundaries of the movie screen, we are ourselves are viscerally react to the overwhelming enormous hulk of a house before us with anxiety about what we might encounter entering such a place.

We in the audience will “arrive” at Manderley three times during the course of the film –here in this scene, as a ruin in the opening dream sequence and in flames at the end of the film. [This was all accomplished through special effects, filming specially designed studio “miniature” models of Manderley, rather than an actual mansion. A further discussion of the set design and special effects will presented in a planned companion web site with the working title “Revisiting Manderley.”] Additionally, the full still images of Manderley’s façade will be flashed across the entire screen several times during the course of film to signify the passage of time.

The Arrival at Manderley: Servants at the Door

The Arrival at Manderley: Servants at the Door

Arriving at the entrance door, the couple is assisted from the car by the butler and footman in formal livery holding umbrellas. Two stone obelisks, mimicking the shape of ancient pyramids, flank the steps up to the carved double door entrance of Maxim’s ancestral home. Unlike an arrival at an ordinary house, an arrival at a mansion in movies nearly always includes a servant-‐ here two of them-‐ to let you in. We have just witnessed in quick succession five of the most oft-‐repeated scenes defining the mansion movie:

(1) the hero/heroine’s journey en route to the mansion,

(2) entering or passage through an external gate or boundary,

(3) the mansion’s facade filling the movie screen,

(4) the protagonist’s response to its first sighting and

(5) the arrival greeted by a servant or servants at the door.

Chapter 7

Entering an Enclosed World:

The Audience Enters the Mansion Along With The Outsider Protagonist

As they enter Manderley’s, the camera follows the couple and the two servants through the double doors. The camera moves backward to record the next shot of Maxim and “I” moving into the entrance hall. Another boundary or threshold is crossed with this passage through the massive arched doorway to the mansion hall. As impressive the exterior was, the interior is always even more imposing. Entry into the house is admittance into another world, hitherto private and unknown. Due to the way mansion movies are filmed, we the audience enter the mansion along with the outsider protagonist. We are on the outside with them and then on the inside with them. In effect, the way this scene and others are filmed, we the audience have been invited to come inside. We are, thus, not trespassers but invited guests or visitors, not voyeurs. We are privy to what is going on, are included and made part of the experience.

The Interior “Wow” Moment: The Great Hall and its Army of Servants

The Interior “Wow” Moment: The Great Hall and its Army of Servants

Once inside, we see what “I” sees – an army of liveried servants lined up several rows deep against the background of the carved architectural ornamentation of the back walls of the mansion’s Great Hall. Paralleling the initial long shot of the mansion’s exterior, this interior scene is blown up and spread across the entire screen. This shot is our, and the heroine’s, first view of the mansion’s interiors. We have some more time to view the details of the huge space with the long shot of the couple approaching the staff. Thus, this is the audience’s interior “wow” moment!

The couple and small army of servants appear dwarfed in the massive Great Hall, emphasizing the house’s overwhelming presence. It is the juxtaposition of the small-‐scale human figures to the vast architectural space that defines the house as something larger than life and asserts its central position in the story. Simultaneously confronted by the vast interior space and the host of servants in full dress before her, “I“ is both astonished and intimidated. She, for the first time perhaps, begins to understand that the “fairy tale” element of her future may be over.

In most mansion movies, a family member is inside the mansion upon the outsider’s arrival. Maxim has no family other than his sister and her husband, who live elsewhere; their reaction to the newcomer will occur later, when they visit for lunch. Maxim did not want a formal reception, but Mrs. Danvers, the housekeeper, (Judith Anderson) made sure the entire staff was on hand and at attention for the arrival of the master of the house. (This traditional formal line up of servants is shown repeatedly on the TV series, Downton Abbey when Lord Grantham returns after an absence or a special guest arrives.) The moment is of great importance in establishing the status and power dynamics and status in the household. There is sizing up going on and the person with status – bride – is actually the one intimidated and feels inadequate.) Composer Franz Waxman accompanies the drama of this pivotal moment as in many other decisive scenes. Their master, Maxim, has brought home a wife. The new mistress, her hair and clothes drenched by the rain is visibly shy and nervous, cowed by her new situation. The insiders, here Manderley’s staff of servants, have also been anticipating this moment. They are seeing their new mistress for the first time; she is not particularly impressive. Any new mistress of the house would have an enormous impact of their lives at Manderley; they must now adjust to this new mistress. They are not at liberty to object in any way and, will accept, for the most part, our heroine as the new head of the house without question. Maxim, the mansion’s key insider, met his second wife on the outside and, after only a short courtship, brought her to his home. He so far has not had any misgivings about the stranger he has made his wife but once home again, he will reconsider the wisdom of his decision to marry a woman half his age who has neither experience with a large house nor managed a staff of servants. For Maxim, the moment is of consequence because he has been away for a long time. Manderley is where he belongs. He, by birth, owns this space. It is his home and he commands it. It is he who is important here and he on whom the servants wait. “I” is of importance only in relation to him.

Mrs. Danvers Sizing Up the New Mrs. De Winter

Mrs. Danvers Sizing Up the New Mrs. De Winter

The formidable figure of Mrs. Danvers comes forward to greet the returning master and his new bride. As Maxim introduces this imposing creature to “I” there is a tingling of tension. By entering Manderley as Maxim’s wife, “I” momentarily shares his importance. With her dripping clothing and wet hair “I” hardly makes an impressive entrance. Her self-‐consciousness and anxiety are fully apparent in her first interaction with housekeeper, who is a visually startling presence impeccably dressed in a floor length black uniform with a starched collar, neatly coiffed and ramrod straight. “I” drops her gloves then hesitantly jostles with Danvers trying to retrieve them. “I” shrinks back in this initial confrontation with Mrs. Danvers, losing the first moment of their what will be their ongoing power positioning. The encounter of the outsider with an entrenched family servant is a scene repeated in many mansion movies; the outsider becomes awkward and stumbling in response to the both the grandeur of the space and the rigidity and formality of the behavior of those who serve the family inside. Hollywood movies often equate awkwardness and dropping things with the outsider, newcomer, or novice. It is visual shorthand, often, but not always, reserved for the behavior of women. The tension between our insecure heroine and Mrs. Danvers, who sees the new bride as a usurper, continues throughout the story. At this point of the film we have add three other plot or scene hallmarks of mansion movies:

(6) entering the mansion, crossing that threshold into another world

(7) the inside” wow” moment-‐ taking in the luxurious interior

(8) the outsider feeling out of his or her league, not knowing how to behave

Chapter Eight

Explorations and Encounters Inside the Mansion;

The Honeymoon Over and Life within the Geography of Manderley Walls Begins

As explained above, an important part of every mansion movie is an outsider’s embarkation on a physical journey in response to some turning point or life event. The physical journey’s starting point is the outsider’s home or place of works in the ordinary everyday world. It ends upon the outsider’s arrival at and entrance into the mansion. The more important journey in a mansion movie, however, is the hero’s or heroine’s psychological journey once inside as he or she encounters emotional and relationship challenges within the geography of the mansion. Concurrently, the outsider’s arrival impacts insiders and sets challenges to their lives in motion.

“I” has left her ordinary world as an employee and companion of Mrs. Van Hopper for a new life as the wife of Maxim de Winter in ancestral stronghold of a home at Manderley. Both Maxim’s and “I’s” lives are irrevocably changed. Danvers, according to Maxim’s instructions, has prepared and freshened new living quarters for the master and his bride. She arranges for the parlor maid to assist “I” in getting settled. Later, Danvers enters the new couple’s quarters while “I” is dressing for dinner to see if everything is satisfactory. When “I” asks her if she is the longest serving person on the staff, Danvers explains that she came to Manderley when the first Mrs. De Winter was a new bride. Danvers’ opinion of her new mistress is lessened further, when “I” informs her that she does not possess a personal maid and meekly requests the services of one of the house maids instead of hiring a personal one. Danvers also wastes no time in letting her new mistress know that that East wing of the house was rarely used, and when so, only for occasional visitors. She tells her new mistress that part of the building has no view of the sea and that it is only visible from the West Wing. (Du Maurier’s heroine in the novel is more acutely aware that Danvers is taunting her; in the novel she understands Danvers’ comments to reflect the “snobbery” of the servant class i.e., that “I” was “no great lady and getting a “second-‐rate room” because she was a “second-‐rate person.”)

Danvers follows closely behind “I” going downstairs to dinner. We see “I” leaving the new bedroom suite, entering a short corridor, up some stairs to another narrow passageway, and finally down the steps to the main landing of the mansion’s grand staircase. As they reach the landing “I” looks across the divided staircase. Danvers motioning to the carved double doorway on the other side, stating it is the West Wing. Danvers reverently states that behind the closed doors guarded by the small dog, was the most beautiful room in the house, of course, the former Mrs. De Winter’s room. The camera lingers a moment on the closed doors, marking the significance of the room beyond.

East Wing: accessed at the end of several dark narrow corridors

East Wing: accessed at the end of several dark narrow corridors

West Wing: wide landing in front of doors leading to Rebecca’s Room

Negotiating Meals at Manderley: Dinner for Two,

Buffet Breakfast Alone and Inspection by In-‐Laws at Lunch

Fortune and Formality: Dinner For Two in the Vast Dining Room

Fortune and Formality: Dinner For Two in the Vast Dining Room

Meeting together for their first dinner at home, Maxim and “I” are seated at either end of a long elaborately set table in a grand and formal dining room. Per Hitchcock’s insistence, here is no dialogue as we see the two main servants, Firth and Robert, serve dinner in choreographed motions. Rather than Franz Waxman’s original composition for this scene, Selznick selected a piece entitled “Pomp and Pageantry” by Max Steiner, which had been composed for Selznick’s 1936 film, Little Lord Fauntleroy. It is a major change of musical style in the movie but for me works perfectly for this scene. Its stately tempo matches the mise en scene of the liveried servants, the couple seated at the far ends of the table, and the elaborateness of the room In his characteristic style of drawing attention to a significant object, Hitchcock focuses the camera on a linen napkin initialed “R de W”. (Although du Maurier’s novel also made the Rebecca’s initials a focus in the plot, it was not done in such an obvious way as done here and later in the film; even the most doltish of servants in any stately home would have know better to deliberately set the table with the former wife’s monogrammed napkins.) As a filmic device they incontrovertibly put Rebecca’s stamp on the house signifying that she remains there past death. They make her omnipresent. We see “I‘s” discomforted response to seeing the napkin as the camera pulls back and up away from her face and ending in a long shot of the entire room from the opposite end we entered. The isolation of the couple sitting at either end of the long dining table is amplified by the dining table’s placement on an area rug made of white polar bear skins, which gives the appearance of an island floating in the center of the large room. I appreciate the dramatic visual effect, but cannot help thinking that, other than in a Hollywood film, a white fur rug would be an unlikely floor covering in any dining room, much less one in a mansion.

The next morning “I,” in coming downstairs on her own, gets lost and has to be shown the way back to the dining room for breakfast. Her slight stature and psychological smallness of her presence at Manderley is emphasized and exaggerated by the image her standing at the dining room door with the doorknob positioned just below shoulder level rather than as normal at the waist or slightly above. Molly Haskell, in From Reverence to Rape: the Treatment of Women in the Movies, notes that Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton used small size as a metaphor for the outsider. Size is also used to make our heroine appear more childlike in her relationship her new environment, as if shrinking within the overwhelming spaces of the house.

“I’s” sense of being a out of place, a stranger in and around Manderley, is cleverly conveyed with the image of her carrying her handbag with her the next morning as she goes down to breakfast. It is as if she were back at Monte Carlo where we saw her as a guest entering the hotel’s dining room with purse in hand. Overwhelmed and alone, she has no appetite for anything at the grand breakfast buffet set out for her on the large sideboard. She meekly asks for coffee, which she later only hurriedly drinks. In a minor continuity flaw occurs in the otherwise elaborate and careful set-‐up of the food and drink. The food in one of the chaffing dishes is realistically shown to be steaming when the lid is lifted, but when “I” purportedly pours some cream and then coffee into a cup, no liquid seems to be poured out at all. Could this be symbolic of her new life with Maxim – drinking from an empty cup?

————–PHOTO

Frith helping “I” find her way through the Great Hall

In most mansion movies at one time or another the outsider (and thus the movie audience) is given a mini tour of the mansion. Mansions are defined in part by having a variety of rooms each with a special name. “I” leaves the dining room and finds her way to the library. When she shudders from a chill, Frith, the butler, tells her that she probably would be more comfortable in the morning room instead, which is the only room where the fireplace is usually lit at that time of day. Frith leads her back though the great hall explaining its importance as a central place in the house, once the original medieval banqueting hall. As he guides her from room to room, Frith informs her that the general public visits the house weekly. These various scenes show her isolation as a stranger in the great house that seems to swallow up anything on the human scale; she is and feels as foreign to the house as one of the weekly visitors. Maxim appears and immediately disappears going off to attend to estate business and she is left on her own, left alone. The audience senses her feeling of dislocation within these large chambers of the great house when the staff is going about their business but she, its new resident relieved from any work activity, is left on her own with nothing to do. The huge house both isolates and encloses her; but she is never to be alone. With the large staff and with weekly visits by the public, Manderley is not inclined to be her a personal or private domain.

The great hall with its huge refectory table is the historic core of the de Winter family’s Elizabethan era manor house. In contrast, the interior architectural ornamentation of the elegant dining room represents the height of Georgian eighteenth century design and furnishings of a stately English home. Manderley’s library, furnished with an assortment of comfortable chairs and settees, seems to function as a grand Edwardian all-‐purpose living room. It will appear later in several important scenes. The morning room is very different from the other very English in style rooms on the main floor. It is very French and feminine in style. Presumably, it was completely refurbished and redecorated by Maxim’s first wife Rebecca. Sitting at the delicate French desk, “I” is overcome by the charming room’s essence, atmosphere and identification as Rebecca’s personal domain. “I’s” underlying sense of inadequacy is stirred up when she finds her predecessor’s monogrammed address book and stationery in place. (These items with Rebecca’s initials were added to the film version of this scene as visual signs of her omnipresence.) When the phone rings and the voice at the other end asks for Mrs. De Winter, she momentarily forgets her new status and identity as Maxim’s wife and replies that Mrs. De Winter is dead. The reminders of Rebecca magnify “I’s” feelings of inferiority, inexperience and jealousy of Maxim’s first wife. Sitting in Rebecca’s domain, “I” accidentally breaks a small porcelain figurine of Cupid. With a sense of fear and shame at her own awkwardness, she hides the broken the pieces in the drawer. Later, her acknowledgment of her responsibility for the accident will be one of the trials she must face to grow into her new role.

On this, her first full day at Manderley, Maxim announces to his new wife that his sister and her husband are coming to lunch to meet her. As previously noted, mansion movies are normally about an outsider entering someone else’s home and encountering the family inside. When “I” arrived there was no one from the de Winter family in residence at Manderley Meeting the family was thus delayed by a day. By virtue of the old tradition of male primogeniture in inheritance of property, Maxim is the sole owner of Manderley. His married sister Beatrice de Winter Lacy (Gladys Cooper), who appears to be older than Maxim, no longer has any rights to live in their ancestral home. Her position in the de Winter household was determined by the birth of her brother. Before her brother’s marriage to Rebecca, she might have served as the acting mistress of Manderley. In the film she and her husband Giles Lacy (Nigel Bruce) are Maxim’s only living family members. They arrive with predetermined notions about the unknown young commoner Maxim has suddenly married. At the luncheon the new in-‐laws look over, question, and evaluate the new bride; their contrasting her with Rebecca is inevitable. More than just a meal is on the menu in mansion movies. Usually the outsider is the main object of attention. The insiders use the occasion to interview and interrogate the newcomer. Meals are used to provide information about and insight into the characters for the benefit of the audience as well.

Beatrice Lacy seems to be friendly and sympathetic but is also somewhat outspoken and insensitive. Her husband Giles is both pompous and awkward at the same time. In making light conversation during the luncheon he asks “I” if she plays golf, or hunts. Then he asks her if she sails. When she answers she doesn’t, in a slip of the tongue he comments, “Thank God for that!” All fall silent and stare in shock. Giles’ very exaggerated expression of chagrin when he remembers that Rebecca died in her sailboat is a bit of lowbrow Hitchcockian humor, a comedic insertion into an otherwise dramatic moment. It does highlight, however, the palpable tension in the house that surrounds the death of Rebecca. After lunch, Beatrice assessing “I’s simple hairstyle and her clothes and clearly finding her deficient in these areas, bluntly remarks that these things were always important to Maxim. The meeting with the in-‐laws, however, ends favorably

After seeing the in-‐laws off, she and Maxim go for a walk with the dog, Jaspar. When she runs off to follow the dog down the cliff above the seacoast perimeter of the estate, Maxim sharply tells her let him go. In hot pursuit of Jaspar, she ignores his words and ends up near a boathouse where she encounters Ben, an old fisherman. She asks Ben for some rope to make a leash for the dog. When he doesn’t respond, “I” dodges into the boathouse to find some herself and discovers a seemingly deserted but fully furnished and decorated room. The frightened and simple-‐minded Ben talks about the “she’ who has gone. When she returns to find Max, he turns away from her in anger. He becomes furious when he learns she went into the boat house’s cottage room, telling her sharply not to go there again. When she ends up in tears at his hostile behavior toward her, she pulls out a handkerchief from the house raincoat only to find it monogramed with an “R”. (This was one of du Maurier’s uses of Rebecca’s initials as shadowing the new bride in the novel. it was presumably left in the raincoat in the past and long forgotten-‐ not deliberately left there.) In mansion movies there is often a contrast house or space much less formal than the rooms of the mansion. The cozy comfortably furnished cottage room is one of those places.

Overcoming Insecurity and Finding One’s Identity in the Mansion

Adrift in her new surroundings, with no moorings, floor plan or guidelines except allusions and comments on how her predecessor did things perfectly, “I’ is abandoned to her own devices. Her attempts to navigate the house on her own are awkward; she feels caught by the staff as she wanders around trying to find her way. These first episodes in her new home are a prelude of what life will be at Manderley: deprivation amidst opulence, boredom and loneliness, no real work to do or purpose. Her husband, once back at his beloved home, is off on his own, fully occupied with matters of the estate. Maxim is seemingly indifferent, selfish and boorish with respect to his new bride‘s situation. Left behind, she is eager to do anything to relieve the emptiness and offers to assist Frank Crawley (Reginald Denny), the house manager, by licking stamps on the outgoing mail. She asks Frank about the neglected cottage room and finds out it was Rebecca’s special hideaway. She inquires about her death alone at sea and he says that Rebecca was not afraid of anything. When she dares to asks him “What was Rebecca really like?” he too drifts into dreamy nostalgia about the deceased woman, describing her as “the most beautiful creature I ever saw.” The specter of Rebecca as an unsurpassable rival arises over and over. Feeling estranged, investigated, and appraised, whether from envy or judgment, “I’s” sense that she is hopelessly inadequate to compete with the ghost of Rebecca become further exacerbated.

Black Satin and Pearls: Belated Coming of Age in A New World

In an attempt to become more sophisticated in image and style, “I” orders a glamorous black gown and has her hair styled. Her husband’s reaction is not positive. She wants to look and be sophisticated; he wants her to look and remain innocent and naïve. Together they watch home movies of their honeymoon in the Library and we see them as a joyful and carefree couple in love. The happy mood of these memories is interrupted by the entrance of Frith, the Butler, who announces an argument has erupted amongst the staff about who was responsible for about a broken china figure of some value. When he leaves, ‘I” confesses that she broke and hid the figurine in embarrassment. He scolds her for her timidity in refusing to admit the accident in front of the servants. When seeing her childlike reaction and fear of the staff, especially with respect to Mrs. Danvers, he tells her she is behaving like an upstairs maid “not the mistress of the house.” She becomes further embarrassed when Frith along with Danvers return to hear Maxim explain that his new wife broke the cupid and “I” has to explain in front of them that she hid the pieces in the back of a drawer. There seems to be a disconnect between his desire for her to remain childlike, dependent and malleable in relation to him and his expectation that she be in charge and authoritative with respect to the servants. The explanation is likely that these are two different realms. He wishes for her to be sweet and compliant as wife to him, of the master of the estate. Nevertheless, he expects her to take charge of household matters -‐ the house and the servants – functions which he sees as pedestrian and beneath his dignity. When she later suggests that he married her because she so inconsequential no one would gossip about her, he erupts in anger about even the idea of possible gossip. One of the tenets of aristocratic or societal mores in mansion movies is avoidance of gossip and scandal. Amoral behavior may be indulged or tolerated, but any such behavior must be discreet.

Maxim moodily muses out loud that he was selfish in marrying her, suggesting that he is thinking the marriage was a mistake. This devastates his young earnest wife. When “I” essentially pleads with him to confirm that he believes they are happy together, it is not within his ability to give her any solace by agreeing. Instead, he despondently says, “Happiness is something I know nothing about.“ (Think of Prince Charles unable to define “what love is” in relation to his wife Diana.) In these moments, her faith in their marriage becomes undone. She continues to believe his enduring love for Rebecca stands between them.

Opening Closed Doors -‐ Entering Rebecca’s Sanctuary

Alone in the library the next morning with Maxim gone to London for the day, “I” notices a window open in the West wing where no one is supposed to be. She later overhears Mrs. Danvers telling a man to leave so the new Mrs. De Winter would not see him. The charming somewhat rakish man is acting quite at home and familiar. He calls Danvers “Danny” and she introduces him to “I” as Mr. Favell. He refuses “I’s” polite offer to stay for tea, indicating he might not be welcome. Then he requests “I” not mention his visit to her “revered husband.” He further identifies himself as Rebecca’s favorite cousin. The strange and surprising collusion between Danvers and the too familiar man slightly shifts “I’s” position; Danvers is now at “I’s” mercy to keep Favell’s visit a secret. “I,” being dealt this temporary upper hand, at once become determined to venture on her own to explore the Rebecca’ room in the West Wing.

Rebecca’s Opulent Bedroom in the West Wing of Manderley

Rebecca’s Opulent Bedroom in the West Wing of Manderley

A Change of Position – Beginning the Transformation from Waif to Wife

Her curiosity, aroused from the beginning, is now going to be satisfied. The closed doors, Danvers’ enticing comments and the dog guarding the passage had tantalized her. Beyond the doors, “I” finds a huge anteroom with floor to ceiling curtains across one end, dividing the entry area and the main bedchamber. A four-‐ poster bed upon a stage-‐like platform dominates the very large and fanciful bedroom beyond the curtain. It is unlike any other of the traditional spaces or rooms in Manderley; instead, it looks like a fantasy stage set in the theatrical art deco style of many 1930’s movies. Out from nowhere appears Danvers who had been waiting from the first to show “I” this room. At the bedstead, she shows off the nightgown case embroidered with an “R” that she long ago had made for Rebecca, pulling out the delicate negligee. Danvers suggests in an erotic manner that her new mistress feel the translucent material and see how her flesh shows through underneath. She pulls out some of Rebecca‘s clothes and points out Rebecca‘s dressing table. There she describes her routines of caring for her precious former mistress in obsessive and somewhat perverse detail. When Danvers says that she has kept everything in place as when Rebecca was alive and comments that she feels that Rebecca spirit is watching everything in the house, including “I” with Maxim, “I” flees the room in terror. “I” is jealous of her dead rival; Danvers acts out of jealousy of “I”. Seeing herself as the protector of Rebecca’s enshrined position at Manderley, Danvers is against “I” taking Rebecca’s place in any way.

Danvers has gone too far. She so grossly oversteps her servant’s role, she unintentionally shocks “I” into a new posture. Rather than exhibiting the melancholy and defenseless posture shown since her arrival at Manderley, “I” suddenly snaps into a new demeanor. She asserts her rightful position as mistress of the manor and demands the respect that it deserves. “I” then marches into the Morning Room, angrily gathers all the reminders of Rebecca from the desk and calls to Danvers to get rid of them. When confronted by Danvers that they were Mrs. De Winter’s things, “I” exclaims loudly, “I am Mrs. De Winter!”

Chapter 9

The Family Truth or Secret Uncovered:

Loss of Innocence

In addition to a formal dinner scene (again, this film not only had a dinner scene, but a breakfast and family luncheon scene as well), mansion movies usually have a climactic elegant party or ball scene. In such a scene, a large space in the mansion is rearranged and decorated for a grand event. Garlands deck the walls, urns are filled with flowers, and a serving table is laden with punch bowl and special foods. Wanting to wear a very special gown at the ball hosting Maxim’s friends and the community, “I” somewhat foolishly takes Danvers’ suggestion that she have a costume made to replicate the gown shown in the life size portrait of tone of Maxim’s ancestors.

Manderley’s Great Hall Transformed into a Ballroom

Manderley’s Great Hall Transformed into a Ballroom

The transformation of the great hall into a ballroom is metaphor for the emotional transformation of the protagonist by virtue of uncovering a family secret or truth. Several truths are to be discovered the evening of the ball and the morning thereafter.

Danvers total lack of respect for her new mistress and her nonconformance to the normal parameters of the master-‐servant relationship, is echoed in the climactic scene in which “I” realizes Danvers trickery in suggesting the costume from the an ancestral portrait for the annual ball at Manderley, reinstated at “I” request. After all her preparations for the ball and dressing in this special costume to please her husband, Maxim is repelled and furious when “I” comes down the stairs to show herself off. He shouts that she must change immediately before any of the arriving guests see her. “I’s” tears and anguish turn into anger when she notices Danvers going into Rebecca’s room and follows her there. Danvers tells her that Rebecca had duplicated the same portrait gown for the last ball at Manderley before her death. When “I” asks Danvers why she hates her, Danvers boldly tells “I” that she can never replace Rebecca, that Maxim will never love her and “I” should just give up and leave. In an act of total malevolence, Danvers tries to encourage the sobbing “I” to jump to her death from the window. This scene is reminder in reverse of the near suicide scene when “I” first saw Maxim ready to jump off the cliff near Monte Carlo. Where “I’s” natural helping instinct was to prevent Maxim, a total stranger, from possibly jumping off the cliff, Danvers’ instincts lead to perverse and wicked berating of “I” in comparison to Rebecca and encouragement to jump. Driven to despair, “I” is almost ready to end her life but recovers her inner strength when she hears an alarm at sea sounded and sees rockets shot into sky to signal for help. Like Maxim’s coming out a trance when she shouted out to him on the cliff, the rockets noise brings “I” to her senses and she runs from the room to change and try to find Maxim.

The alarm, flares and rockets were activated by a large ship in the harbor upon discovering the offshore wreckage of Rebecca’s sunken sailboat with a body aboard. “I” finds Maxim in the stone boathouse cottage. He tells her what he has feared all along; Rebecca has won. When “I” says she will help him even if he doesn‘t love her, he finally realizes that all along “I” wrongly has believed his moodiness and misery was because he had loved Rebecca and lost her. Instead, Maxim for the first time admits he not only did not love Rebecca but actually hated her. He tells “I” that Rebecca never loved him and had cheated on him from the beginning of their marriage, but he went along with a pretense of being happy to protect his family name from scandal. He tells her that they are going to find a body on the boat. When “I” doesn’t understand the import of this, he explains the body is Rebecca’s and he knows this because he put her dead body in the boat and later deliberately identified and buried an unclaimed drowned woman’s body in the family crypt. He explains that on that fateful night, he had come to the cottage to confront Rebecca, thinking she was meeting her lover Favell, the night that she died. Rebecca was alone. When he told her he had had enough of the sham of their loveless marriage, Rebecca told him she was pregnant with another man’s child and gloated that that child would be the lawful heir to Manderley as no one would believe otherwise due to their successful pretense of an idyllic marriage. He said that Rebecca continued to taunt him, questioning what he was going to do about it and asking “aren’t you going to kill me?“ All the while Maxim is telling “I” what happened that night, the camera slowly scans the interior space of the room where the confrontation took place. He recounts that he must have struck her but she remained standing and smiling. He says that she then came toward him and stumbled and hit her head on some ship’s tackle. She was on the floor dead. He further confesses that in a state of panic about the consequences and he hid her body on her boat and sank it

Chapter 10

Transformation & Resolution

“I” is transformed by her husband’s confession. Beyond the horror of what happened, “I’s” abiding thought is that Maxim never loved Rebecca. Rebecca’s power over her as a rival has been vanquished. “I” pledges to stand by her husband whatever the consequences. The movie, otherwise a fairly loyal “picturization” of du Maurier’s novel, is unfaithful in this very important detail. In the novel, Rebecca’s death is not the result of an accidental fall in their struggle. Rather, Maxim deliberately shoots Rebecca as she taunts him with the falsehood that she is going to bear a child who will inherit Manderley. Although he initially thought about testing these limits, Selznick knew the film would never be approved by Joseph Breen, the chief administrator of the Motion “Rebecca” Revisited: An In-‐Depth Ten Chapter Study 4 Picture Industry’s self-‐censoring Production Board, without this major change. Whenever I read the explanation about the fussy production code, however, I have always thought the result was not unreasonable. I cannot see the average woman or man in the movie audience easily expecting the couple to have any hope of happiness if Maxim was guilty of homicide, even if conceivably justifiable. How could a young wife live with the knowledge that her husband shot his first wife in fit of anger? What was Rebecca’s crime? Adultery? Promiscuity? Mental Cruelty? Arrogance? Even if such behavior by a woman might be determined a non premeditated “crime of passion” and charged as manslaughter with less punitive consequences in western societies, it seems unlikely that it would be acceptable to the general movie audience, even if overlooked in reading the novel. What if, in the future, “I” stepped “out of line” in some other way, would he someday kill her too? Could the male lead go unpunished or the heroine really remain with him, if she knew he was a killer?

Nevertheless, despite Rebecca’s death and Maxim’s cover up, “I” is so elated to know Maxim did not love Rebecca at all that she seems to shrug off any concern about the truth other than how Maxim sees it. She is energized and empowered in learning this secret because it explains all the ambiguity in Maxim’s behavior towards her. Whatever “I” lacks, she no longer has to compete with Rebecca for his love. Later the next day, we see the couple in the library embracing each other for the first time locked in a passionate kiss. This prospectively implies that their relationship triumphs and perhaps life at Manderley will proceed on a positive trajectory in the future. But our memory of the dream sequence and the haunting word of “I” the narrator undermine any realistic belief in a traditional happy ending.

Resolution: The Inquest Finds Death by Suicide

The Destruction of Manderley by Fires

The Suggestion of Permanent Self-‐Exile in the Dream Sequence

Offers A Not So Happy Ending

When evidence is presented at the ensuing inquest that the boat was deliberately damaged in order to sink it, Maxim suggests to the local authorities that the scuttling of the boat was at Rebecca’s hands. Favell, Rebecca’s lover, believing foul play -‐ not suicide -‐ was involved, tries to blackmail Maxim with a letter showing Rebecca planned to meet him at the cottage that night. Maxim, however, calls in the police and Favell turns the letter over to the inquest. It is discovered that, instead of being pregnant, the doctor Rebecca consulted the day of her death told her she had incurable cancer. Thus, the inquest ends with a finding of suicide. Favell phones Danvers to give her the news. Danvers, knowing that she can no longer prevail, sets fire to Rebecca’s room and is killed by its falling ceiling. We see Danvers setting the house on fire while “I” sleeps. Maxim, returning to Manderley from the inquest along the same driveway we saw at the outset of the film, sees the sky alit from the flames and cries out “That’s Manderley burning!” But when Maxim arrives home he finds “I” safe outside. She tells her husband that the news of Rebecca’s cancer and the finding of death by suicide drove Mrs. Danvers crazy. We see the house destroyed by fire and the camera zooms in on the bed covers and the initial “R” on the pillowcase as the flames engulf it. Thus, the story begins and ends at Manderley. We are brought back to the image in the beginning of the story‘s wistful dream scene with Manderley in ruin. Our hero and heroine survive but the Hollywood happy ending, if there is a semblance of one in this film, is not to be at Manderley, as it exists no longer. Along with the haunting presence of Rebecca, Manderley is destroyed. Danvers is dead as well. The movie ends with a reprise of the narrator’s voice saying, “We cannot go back to Manderley again”, but due to the last scene in the library and their embrace at the film’s end, we feel a glimmer of hope that the couple might find lasting happiness together elsewhere. It is interesting to note the other changes in the story beyond the explicit way Rebecca dies. In the novel, Danvers survives; Maxim and “I” spend the rest of their lives as homeless exiles, living in small hotels to avoid meeting people that they knew before. The shadow of Rebecca thus follows them. Eventually, Maxim has an accident and “I” becomes his caretaker; her hopes of having children will not be fulfilled. That may be enough atonement necessary for a popular novel but it wouldn’t do for a movie.

Do mansion movies reflect real life or are they myths? Myths are elaborate ways of telling familiar stories, with the larger-‐than-‐life ancient gods and goddesses playing out human foibles. The Cinderella style beginnings of the depiction of Maxim’s and “I’s whirlwind romance and marriage reminds me of Diana Spencer’s marriage to Prince Charles, her impossible dream coming true. Diana was a shy, young girl, albeit from an aristocratic family, who married an older man she hardly knew. She had to adjust to the rarified and formal life as a member of the royal family, learning the ropes with the public watching her every move. There too, was the shadow of his former lover. We know the tragic ending of that saga. The movies not only reflect our culture but also influence it. They define what we desire and create expectations in all of us about romantic love in such a way that the reality of marriage once the honeymoon is over can hardly fail to disappoint. Diana, a romantic who came from a broken home, believed that marrying her prince would make all her dreams come true.