Art Reflecting Life Reflecting Art

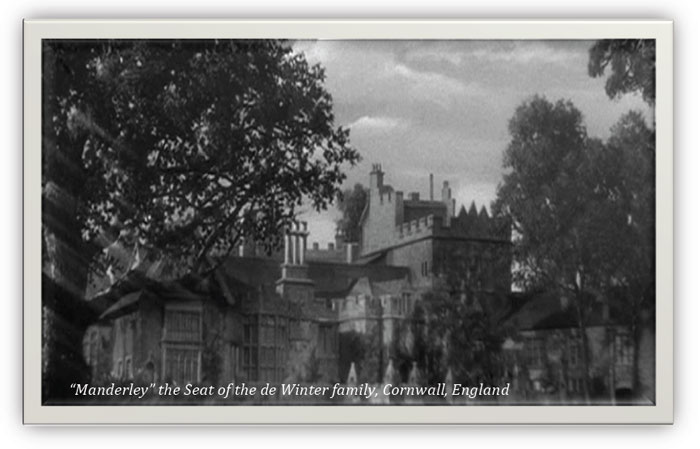

In Daphne du Maurier’s 1938 novel and Selznick’s and Hitchcock’s classic 1940 film, Rebecca, the story begins with a nostalgic dream sequence about returning to Manderley, her marital home, and finding the winding road to the mansion overgrown and the mansion in ruin. When the heroine recollects her meeting Maxim de Winter, her husband to be, for the first time she tells him that she once bought a postcard of Manderley while on vacation with her family when she was a child.

These two particular incidents in Rebecca had their origin from personal experiences in the life of Daphne du Maurier and in their own way have evoked in me a personal connection to both the novel and the film. In writing about Manderley in Rebecca, du Maurier was in part inspired by her near life-long relationship to a house called Menabilly. As described in another section of this website, she became entranced by Menabilly when she found a picture of it in a local guidebook when she was a young girl vacationing in Cornwall with her family. After many years of exploring the overgrown grounds of the Menabilly estate as a visitor, in 1943 she eventually was able to lease the house and restored it.

In 1942 my family bought a turn of the twentieth century mansion at the center of a country estate in southeastern Pennsylvania. The estate was taken in receivership by a bank in the middle of the Great Depression and, up to its sale, the house was left vacant, with roadways, gardens and grounds totally overgrown. The bank had made a 16 mm film of the property in 1938 and we acquired possession of the film in purchasing the property. As compared below, the deteriorated silent film footage of our estate is eerily similar to the opening dream scene in Rebecca. The only difference is that our mansion, though in disrepair and neglected, was not a burnt-out ruin.

[one_half][/one_half] [one_half_last]

A set of digital stills from the dream sequence of the 1940 motion picture Rebecca in which begins with the heroine narrator speaking du Maurier’s famous novel’s opening words, “Last night I dreamt I was back at Manderley again” and which ends with the camera panning and focusing on the ruined shell of the burned mansion

[/one_half_last]

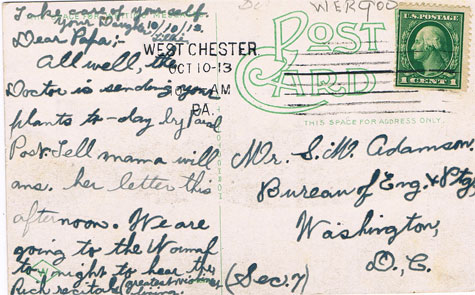

Postcards: Real and Fictional

[one_half]

[/one_half] [one_half_last]

[/one_half_last]

The other unusual personal connection with the presentation of the mansion in the film and the real life mansion in my life is that like the fictional postcard of Manderley that the heroine of Rebecca purchased as a child, illustrations of Greystone were made into publicly-sold postcards in the early 1900s soon after it was built. Over the years I have collected the various colorized images of our house that were printed and sold as postcards a hundred years ago. They still show up from time to time at stalls selling postcards and other print ephemera at antiques stores and flea markets. It is an odd experience to go around the country and find a postcard featuring a picture of a house your family has personally owned and lived in.

I have tried to uncover the real mansions that the authors of the literary works were inspired by in writing their mansion centered stories Once the houses at the center of the stories were envisioned and recreated for the film adaptations of those works, however, the reel images of the mansions are the images we remember. I made the mock postcard of Manderley, shown below, using the illustration of the miniature model of Manderley seen in the 1940 film. In the film Frith the butler takes time to explain to the new Mrs. de Winter that the public are allowed to visit the downstairs rooms of the house on a weekly basis. This reflects a long English tradition that many stately homes, like the fictional Manderley, would be open to the pubic on a limited basis. People would know about such grand homes, long before the advent of photography and postcards, by word of mouth and from printed etchings of famous houses.